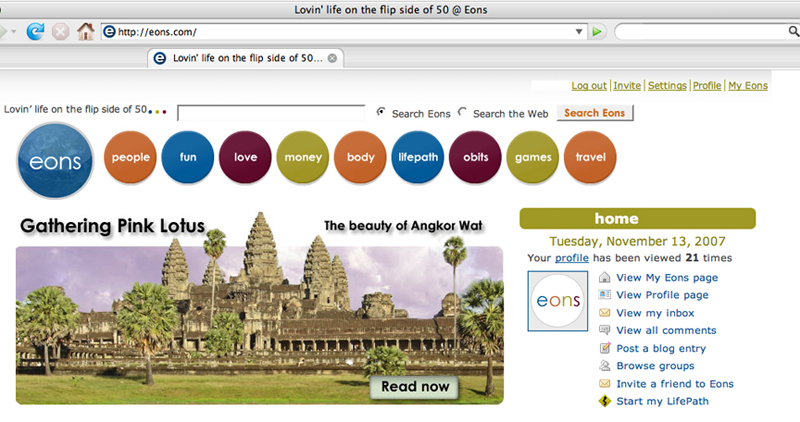

The woman's head glided along the surface of the water next to a bouquet of pink lotuses. As she gathered the plants in the pastels of the morning light, she moved through the lake's reflections of the famous Angkor Wat and sent the tower images rippling...

I watched her in the undulations of the ancient temple while I ate my first breakfast in Cambodia, sitting near the jungle's edge -- not something I ever would have imagined as a college student in the late 1970s, when the Khmer Rouge's brutality created the "Killing Fields" and decimated the Cambodian people and culture. The words Khmer and Cambodia had no alluring associations for me then. I didn't know that the Khmer civilization of the 9th to 12th Centuries left what many consider to be the largest religious monument on the planet (Angkor Wat) and created what some claim was the largest city in the world at the time (Angkor Thom).

Watching the sunrise over the temple was part of my own dawning of realization, as the guide talked about a people who loved art, entertainment, dancing, and games, and who embraced various world views that combined forms of indigenous animism, along with the Indian and Chinese influences of Hinduism (Brahmanism) and Buddhism. The lotus flower was, and is, a symbol of both religions for beauty and purity that can rise above the muck and mud they grow in.

The ancient Khmer were not bent on exploration, foreign trade routes, colonization, or any of the other activities that make an empire famous beyond its boundaries. They were interested in beauty and pleasure more than science or invention. They did not enrich the Western world with Homer, corn, algebra, calendars, or enduring cultural legacies like those of other great civilizations. They did, however, leave buildings as compelling to the traveler as the pyramids of Egypt and the mazes of Machu Pichu, but with more stories carved in the stone.

The Khmer buildings that survived the mire of war, politics, time, and the jungle make them like precious lotus for tourists to gather as experiences.

Organizations around the world are helping to restore and rebuild approximately 70 sites left from the Khmer Empire. People are the other great inheritance from the Khmer Empire. About ninety percent of the population living in the Kingdom of Cambodia today are descendents of the Khmer, and the language they speak is called Khmer. After only a few days there, and seeing only a fraction of the potential sites, the phrase Khmer now has wonderful associations for me.

Every morning, when my husband and I set off from the city of Siem Reap with our kind guide and skillful driver, we had a sense of discovery and exploration. We were rewarded with scenes worthy of National Geographic, including huge tree roots gnarled around sculpted entries, hammocks hung under homes on stilts in the kampong or country way, and boys riding water buffalo in rice fields. Parts of the agricultural lifestyle of Cambodia has changed little since the Khmer Empire converted to a more labor-intensive schedule of three rice crops annually, instead of two, to support a larger population. The greatest source of protein, then and now, is the fish of the picturesque Tonle Sap lake and river system, where thousands of people live in boats near floating churches, schools, pool halls, and markets.

ANKGOR WAT

The three-terraced masterpiece called Angkor Wat, the iconic site pictured on Cambodian money, was completed just before Notre Dame was started in the 11th century. While the Parisian Christian building is shaped like a cross, the far larger Angkor Wat has a cosmological architecture with moats that represent celestial seas and terraced towers that recall sacred mountains. The walls and archways portray art, history, mythology, religion, and botany.

The dramas and details of daily life including tools, fashions, and musical instruments are also carved into the building. There is great power, select beauty, and even humor on the walls. Our Cambodian guide Bunsarng points out how a live turtle being carried by one person is biting the posterior of another fellow. He also solemnly translates the epic stories in stone of imaginative parables and real battles. Not far away he can point to bullet holes of more modern warfare that occurred a millennium later.

After walking the long corridors through the past, I stood in an inner courtyard. Looking in one direction, I saw the gracious humility of a shaved nun, sitting beneath a large Buddha statue, keeping the fires and incense going in a place where uncountable prayers had probably wafted up with the scented smoke through the centuries. Even after Thai and Cham (Vietnamese) invasions forced the Khmer to abandon their centers in the middle of the 15th century, Buddhist monks kept the grounds cleared around this temple and continued to worship. Now, the nun offers her incense to passing visitors, so they too can add their devotions.

When I looked in the other direction, I saw a young boy exuberantly running by a row of the topless Apsara deity statues. He stopped at each one just long enough to cup his hands over the breasts and rotate quickly before moving to the next pair, adding his hands' oil to the darker sheen of that part of the statues. Clearly the dancing angels had been "admired" by many before him. The boy's mother admonished him, and he sheepishly stopped. Behind them, the father lifted one hand to an Apsara and, when he thought no one was looking, left his mark just as his son had moments before.

Angkor Wat still has over 1,800 Apsara statues by one count, most with different hairdos, headdresses, and telling postures of various hand and feet positions. During the Khmer Empire, there were many more live female dancers and artisans that enjoyed royal court life.

ANGKOR THOM

Not far from Angkor Wat (temple) is Angkor Thom (city), which was arguably the largest city on the planet in its heyday, when people would go to its Elephant Terrace to mount the great steeds. Bas reliefs still honor the animal that could navigate terrain no wheel could conquer. Nearby is a platform for royalty where they could watch the tight ropers go from tower to tower, a regular part of celebrations. Just outside the walls, monkeys now scramble about looking for tourist hand-outs.

Angkor Thom is full of story and history and mystery like any great abandoned city, but what uniquely grabs your eyes and heart are the faces of the Banyon Temple that is in the geographic middle of the city (about a mile from the South Gate). There are 54 four sided towers, each side "facing" a cardinal direction with a large captivating face. Our guide tells us the four faces stand for "Charity, Compassion, Empathy, and Kindness." Scholars who debate their inspiration think the faces all depict King Jayarvarman VII looking omnipotently over his people (Big Brother art long before the Stalin era.)

We can't see the backs of these giant heads the way you can the more elongated Easter Island heads or the colossal Olmec heads of Mexico. Time has endowed unique patinas and markings on the Khmer faces. Some look like large puzzles reassembled; others gaze back at you, very much intact. Some appear to have the wisdom of Buddha; others look slightly amused or sad. They all appear to have a secret they are the verge of sharing. I want to keep staring gently at them, hoping I will hear it.

BANTEAY SREI

These beautiful restored ruins are also called the Citadel of Women, not because of the pink- and rose-colored hues of the rock that are different from the sandstone browns of other sites. Our guide also tells us it's not because of the many female deities and apsaras carved into the pinker rock. He thinks it is because, "Details were women's work. They are good at it and there are so many details." And they are exquisite details, finer than lace. One written history says the site was named "Citadel of Women" because it reflects a peaceful reign when beauty was encouraged.

When we arrive, a downpour begins and what looks like a running parade of colorful umbrellas bursts forth from the one entrance, a moving necklace of international tourists. We wait, then go in to have the "Jewel box" archeological site to ourselves. Although it was further away, with some dirt roads, and harder to get to, this site is easier to see because of its smaller size and more complete restoration. We absorb a lot of rain, but also a lot of wonder.

We smile at the Deity of rain that looms over one of the inner entrances as we get wetter and wetter, and see the doors get smaller and smaller signifying increased humility as you reach the center. We are able to touch 9th century Sanskrit on an upright pink tablet and to see the palace without any other humans to remind us what year it really is. By the time we leave, all the pools that were empty when we arrived, are full.

PILGRIMMAGE

Visiting the Angkor sites felt more like a pilgrimage than a vacation destination. Like many pilgrimages, some suffering was involved, but nothing like prostrating on the ground every six feet. Most airlines don't fly into Cambodia directly, so we needed to switch carriers then wait in lines when we entered the country to get our visas which aren't available ahead of time.

Taking pills is recommended to avoid malaria. There is a Dengue Fever outbreak in Cambodia, and other diseases spread by mosquitoes, so I coated clothes in insect repellant before travelling, and slathered myself daily. We saw a dead black scorpion and a dead poisonous snake.

The humid, hot equatorial climate offers no winter or fall weather. The rains drench everything in intense downpours, and tropical skies bloom in-between. To see more remote ruins, I clamored over rocks and hiked on paths through the jungle. I was sometimes uncomfortable with heat rashes and sweat in places I didn't know I could sweat.

It was all worth it to me. The discomforts were a mild cost for wonder, reverence, and awe, and so much less than what people in other eras had to endure to see the magnificent structures (including camping and, sometimes, long elephant rides crunching over the jungle). In our times, the day can end with massages that only cost $15 an hour in modern, cool hotels.

The truth is, I missed spotting any live snakes, but saw many huge sculpted ones as symbols on the walls and gates. And the insects I saw that were most plentiful were beautiful tropical butterflies. Some even landed on my hand.